The Foundation of Christian Apologetics: Towards A Revelational Epistemology

Presuppositional Apologetics is revelational, theological, and philosophical, beginning in its substance and self-consciously from the God of the Bible, whereas Classical Apologetics, in terms of its internal methodological ordering, is philosophical and theological, yes, but only accidentally, so to speak, revelational. The evidence for the latter is found in the fact that so much of Classical Apologetics is wedded to natural theology, which distinguishes strongly between what can be known by unaided reason and what can known by revelation, a posture which is shared between Christian, Jewish, and Muslim theologians, not to mention Neoplatonism, certain schools of Hinduism, and still others. It is therefore not simply a question of the use of "Aristotle," which as such is a matter of relative indifference, nor of general revelation simpliciter, which is to say the disputed import of that which impinges upon man's senses from the natural world, but of what ultimately distinguishes and decides between all of them: special revelation. As Herman Bavinck affirms, "Our knowledge of revelation, both the general and the special, comes to us from the Holy Scriptures" (The Wonderful Works of God, pg 79). In other words, the determining factor deciding the problem of knowledge is not reason per se, but God speaking in Scripture. And so it is not merely that we must end there at Biblical Revelation but that we must also begin there, at the point wherein the divine mind and will of God decisively and authoritatively interject themselves, i.e. the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments.

The foregoing highlights why reason as such is occasionally called by some a "prostitute," because Christian, Jewish, and Muslim theologians all equally “employ” her to prove their case, not to mention atheists and others. Thus reason, for all its God-given worth, is in an ultimate sense inconclusive. For there is no intra-natural umpire that referees the disputes amongst the reasonings given by natural theologians, whether between Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or others. This is one motive, perhaps not incidentally, why Romanists lean on an appeal to Papism and the Byzantines to Synodalism as their cosmic epistemological guarantee. But, since there is no intra-natural umpire, not even unaided reason supplying this, then there can be no decisive use of natural theology (which we might characterize broadly as those theologies which do not begin with revelation, a further subset of those being ones that seek to end in the affirmation of some particular revelation). The reason for this being that there is, at some point, an appeal to authority in all disputes, for the urge to have a referee in disputed matters is deep and abiding in all people, a feature of the imago Dei and man’s consequent will to pursue objective truth and justice. But reason cannot vouchsafe to itself that authority. Reason must submit to truth as her standard, but Ultimate Truth, i.e. God, being infinite, is transcendental to and inaccessible to finite, unaided reason, whether fallen or not, requiring the asymmetrical inbreaking of truth, i.e. of revelation, into the realm of reason in order for ultimate truth to be knowable. Even Adam in the Garden was graced to know the Lord.

There is thus an implicit ambiguity and irresolvable agnosticism that attends, like a shadow, all unaided use of natural theology, which gives birth to all sorts of philosophical goblins like radical skepticism, rationalism, idealism, Hegelian dialectics, pragmatism, et al. For, apart from the decisive voice of God speaking, no unaided human use of logic escapes the inexorable human use of doubt. For doubt is not itself a content but an open process requiring content, any content. For all content can be subjected to the doubting process, whether that be unto solipsism or nihilism or monism, or even to the doubting of doubt, or to the doubting of doubting of doubt, etc. Of course, this is not to say that Christian Revelation is irrational or opposed to reason, but to observe that reason as such does not possess the requisite intrinsic authority to ultimately determine the case. What is more, “The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Corinthians 2:14 ESV). In other words, the fallen, unregenerate man, which is to include the whole man, including his rational powers, cannot sympathetically receive revelational truth. It is not, however, that such truths are experienced as intrinsically irrational or unintelligible, but that they are repugnant. This is part of why God wants to hold everyone accountable, in order to stop our mouths (cf. Romans 3:19), for man's collective and fallen speaking is but a wild cacophony. As the Apostle Paul declares:

Now this I say and testify in the Lord, that you must no longer walk as the Gentiles do, in the futility of their minds. (18) They are darkened in their understanding, alienated from the life of God because of the ignorance that is in them, due to their hardness of heart. (Ephesians 4:17-18 ESV)

In other words, the fall of man may not undo his per se capacity for reasoning, but the internal alienation he experiences as a consequence of his inborn alienation from the principle of all truth, which is the all-holy Trinity, makes it so that, however hard he tries, fallen man will inexorably end up significantly and even fatally distorting the total process that would otherwise seek to obtain and assert ultimate truth. Thus the idea of mounting upon the fallen wings of reason in order to ascend to ultimate truth is ever unworkable, because although in fallen man reason is still reasonable, the fractured unity of fallen man is such that it ever works to undermine reason's use, so making his use of reason profoundly tragic “because of the ignorance that is in them, due to their hardness of heart.” Thus “darkened in their understanding” and internally “alienated from the life of God,” it becomes in this sense a matter of relative indifference whether man's reason is or is not damaged by the Fall, for the total man himself is so wounded such that even true efforts by an ostensibly pristine reason would still “miss the target” because of internal ignorance, the passions, and the hardened heart’s effect on the reasoning mind. It is clear to all men of experience that reason does not reason in a vacuum, but is touched in innumerable places by motives known and unknown. Even a mystery to himself, it is not as if a man can simply call forth true thoughts at will.

But if any given use of natural theology assumes a regenerated mind, heart, and will, then the thesis of revelational epistemology is vindicated. For, regardless of the reasonableness of man's reason, the especial problem of natural epistemologies is the peculiar nature of fallen man's finitude, his deep alienation from the infinite God who is absolute Truth. For finite minds operating independently cannot rightly approximate or accommodate the infinitude of God, and so require as their only proper epistemological foundation the self-revelation of God in Scripture, and the indwelling of the Holy Spirit by faith, in order to have the necessary data and position (for access to truth implies having right standing with relation to God, i.e. justification) so to attain certain, true knowledge. The very nature of the human use of logic implies its relativity and finitude, and as such it cannot get "above" or "behind" the absolute and infinite God in order to "prove" Him.

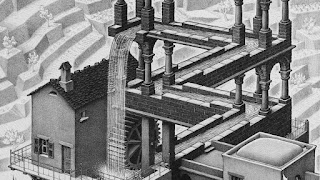

Yet, as an effect consequent to the Logos, logic cannot start with itself and ever hope to arrive at its own presupposition, its own necessary precondition, which is the error of rationalism. For, not unlike doubt, logic is a process, a kind of machinery, so to speak, that requires content and context for its operation. But this content and context could even be a kind of Alice in Wonderland, or a "Marvel Universe," which is to say a kind of universe of relative nonsense within which logic operates in a sphere disconnected from reality, an approximated world which logic cannot of itself alone either discern or escape. In other words, disjointed from its ground in the transcendental Logos self-revealed in Scripture, logic cannot extricate itself from the “marvelous effect” wherein logic is made to serve simultaneously both the deeply serious (e.g. “Off with his head!”) and the deeply absurd (e.g. “a very merry unbirthday”).

Truth's transcendent nature means that truth is ultimately causative of logic, its necessary precondition. This is to say the effect, which is logic, cannot authorize its own cause, which is truth. In this way logic can be seen as an operation of the image of the Logos in man, meaning the Logos is axiomatic to all uses of reason and so cannot be made the subject of reason’s proof. But this means that God cannot be subjected to inference or deduction, can never be a mere conclusion of reasoning, for their authority can only derive from that which they must ultimately submit to. God is thus a necessary inference, not a consequence of inference. It is analogous to how reasoning presupposes Reason, and so cannot prove Reason through a specific act of reasoning, but rather must presuppose it in order to reason at all.

To close, man, as an instance of being, of derived being, cannot prove Being Itself. As a pot cannot prove its own potter, only infer him from the fact of being a dependent creature, so man simply must infer His Creator, which is the knowledge by which man is made to be without excuse. But beyond the certainty of this necessary inference there is, apart from special revelation, no possibility of certain knowledge of who this One is, which throws all other knowledge into an ultimate ambiguity that natural theology, tragically, cannot umpire. In a sense, because of His aseity, God is the only truly brute fact, the one that stands concealed above and behind all other facts. Truth must therefore break in and be given directly by this One whose truth it is, who is Truth. Natural theology, then, and Classical Apologetics insofar as it is made to depend upon it, can therefore only come in as ancillary and supportive tools in the hand of Presuppositional Apologetics, after Presuppositionalism is acknowledged as primary. In sum, revelational epistemology, hence presuppositionalism, is the necessary precondition both for knowledge and, as a consequence, for apologetics, including Classical Apologetics.

-The Reformed Ninja

Hello Joshua,

ReplyDeleteI'm writing to you from Cartagena, Colombia. I am a Reformed Presbyterian pastor (https://iglesiareformadanaciondedios.com/ministries-all/) in this city, and I also manage a presuppositional apologetics website in Spanish (https://www.presuposicionalismo.com/).

This week I came across your testimony and your books. They are truly wonderful. I am very interested in understanding the historical roots of presuppositionalism, and I came across your book on Irenaeus.

I have a podcast in Spanish about apologetics and theology. Could we collaborate on a podcast to talk about the presuppositional apologetics of Irenaeus? That would be a great blessing for the Spanish-speaking community! We have a translator for the recording.

Could you share your email with me? Or if it’s easier, you can write to mine: joseangelrz16@gmail.com

I look forward to hearing from you.

God bless you.